Figure 1: Click on image to enlarge

Figure 2: Click on image to enlarge

Figure 3: Click on image to enlarge

IMAGE OF THE WEEK 2012

WEEK 13

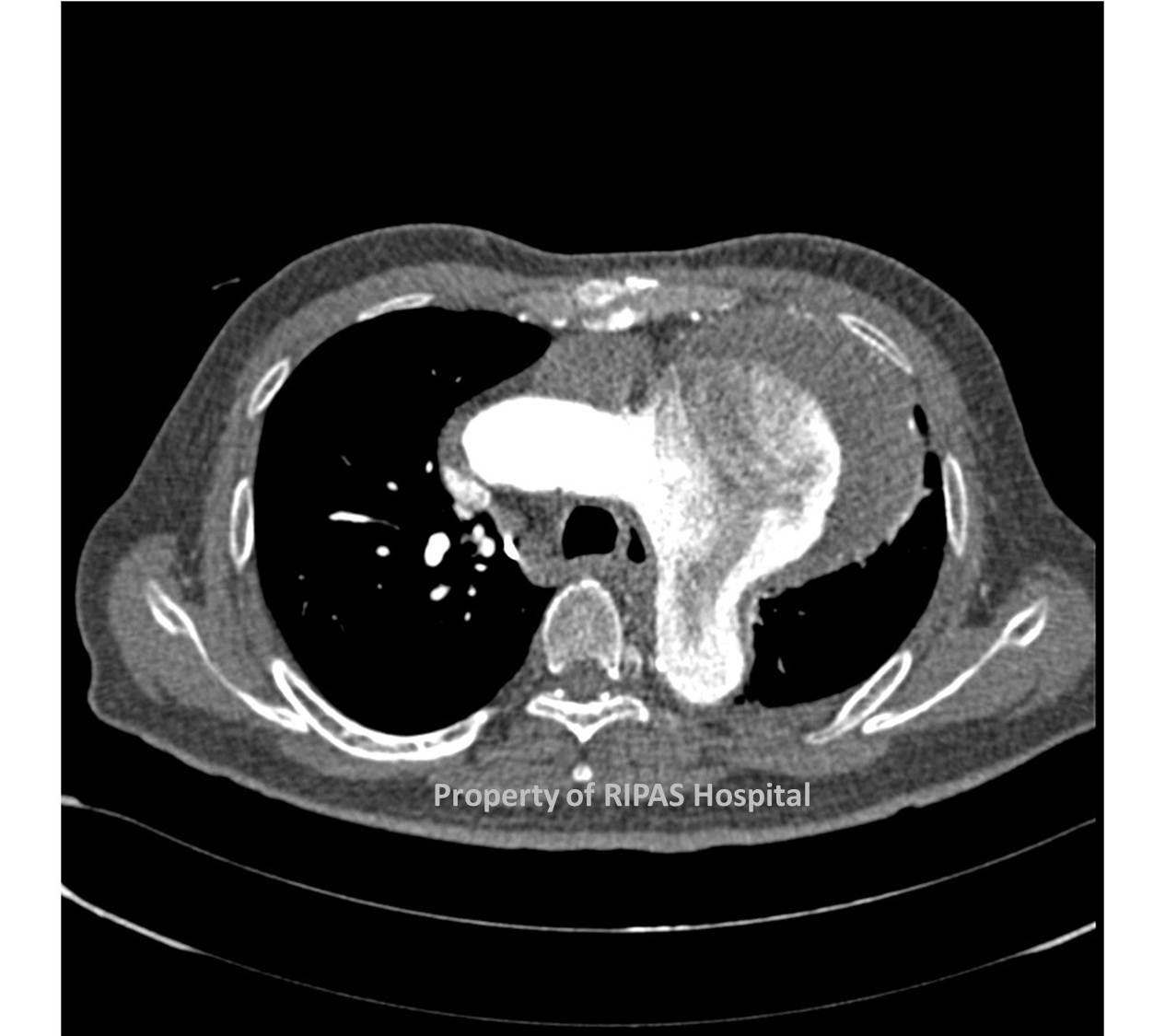

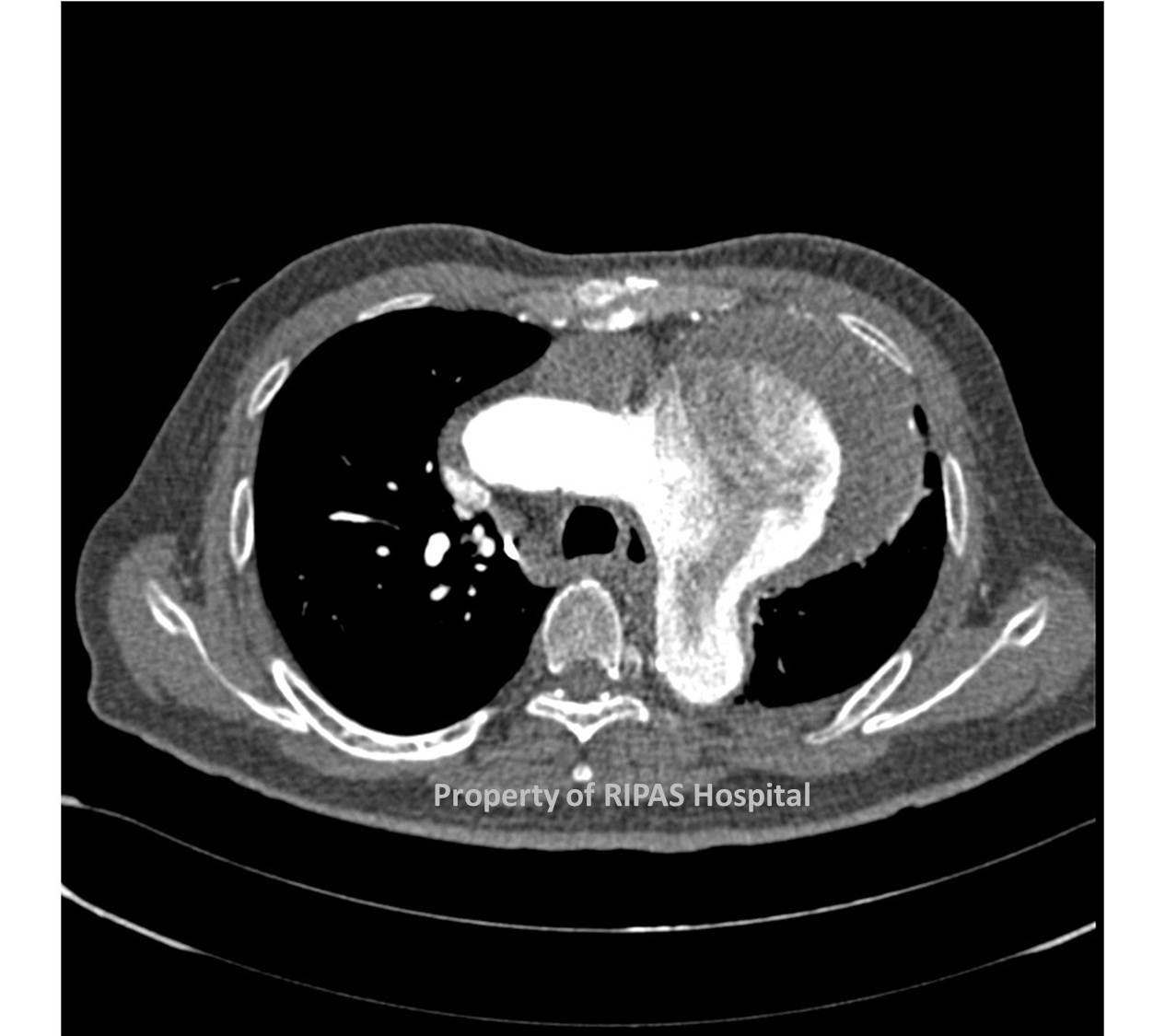

DESCENDING THORACIC ANEURYSM

|

||

|

Figure 1: Click on image to enlarge |

Figure 2: Click on image to enlarge |

Figure 3: Click on image to enlarge |

Descending thoracic aortic aneurysms (DTAAs) can arise at any portion of the aorta just after the origin of the left subclavian artery up to the diaphragmatic level. Involvement beyond the diaphragm into the abdominal aorta are catagorised as thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms (TAAAs).

Aetiologies of DTAAs include nonspecific medial degeneration, dissection, connective tissue disorders (rheumatoid arthritis, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Marfan syndrome), aortitis (Takayasu’s aortitis, giant cell arteritis), coarctation and sepsis (mycotic aneurysm).

Most DTAAs are primarily the result of age-related medial degeneration, characterized by elastin fragmentation and fibrosis with increased collagen which reduce aortic wall integrity and strength, leading to fusiform dilatation of the descending thoracic aorta. In some cases, however, the medial degeneration produces saccular dilatation as seen in Figure 1, although saccular aneurysms are more commonly associated with a septic foci in the aortic media resulting in destruction and weakening of that particular portion of the aorta and ultimately saccular dilatation.

Connective tissue disorders have a genetic origin and are characterized by defective components of the extracellular matrix, such as fibrillin in Marfan syndrome and collagen in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. In Marfan syndrome, fragmentation of the elastic fibres and deposition of extensive amounts of mucopolysaccharides produces abnormal elastic properties, which predisposes the aortic wall to dilatation.

Most DTAAs are incidentally diagnosed and patients are commonly asymptomatic (43%) as is the case associated with figure 1-3. Chest radiographs taken to evaluate unrelated problems may show widening of the mediastinum, specifically the thoracic aortic shadow. As in this case, the patient was evaluated for pulmonary tumour due to the size and location in the left upper lobe.

Although DTAAs remained asymptomatic for long period of time, most will ultimately become symptomatic just before they rupture. Pain radiating to the back between the scapula is fairly common, particularly due to sudden enlargement of the aneurysm. Other symptoms are related to the pressure effect of the aneurysm on the surrounding structures such as stridor, wheezing, cough, haemoptysis, dysphagia, GI obstruction and bleeding. Due to the close proximity of the left recurrent laryngeal nerve, patients can present with hoarseness of voice due to stretching of the nerve by the enlarging aneurysm. Neurologic symptoms such as paraplegia, paraparesis or both can be the result of thrombosis of the intercostal or spinal arteries.

Investigation of choice is a CT angiogram of the thoroacic aorta and using the inbuilt software programme, a 3D image of the DTAA can be created to better appreciate the size and location. MRI does not add any more to a CT angiogram although it is useful in patients with renal impairment.

Current treatment options include TEVAR or Thoracic endovascular aortic stent repair, which is a minimally invasive repair technique involving the introduction of a pre-fabricated steel or nitinol stent via the femoral artery. Operative risk is reported to be less than 3% but complication such as endovascular leak can occur. Open repair with or without left heart bypass is the time tested technique but carries significantly high operative risk ranging from 5-25% depending on the experience of the unit. One of the major complications is paraplegia associated with either techniques but the use of CSF drainage has help to reduce the rate of this complication.

Image and text contributed and prepared by

Dr Ian Bickle, Department of Radiology, and Mr William Chong, Thoracic unit, Department of Surgery, RIPAS Hospital, Brunei Darussalam.

All images are copyrighted and property of RIPAS Hospital.