IMAGE OF THE WEEK 2013

WEEK 5

MANAGEMENT OF DISLODGED

PORT-A-CATHETER

|

|

|

|

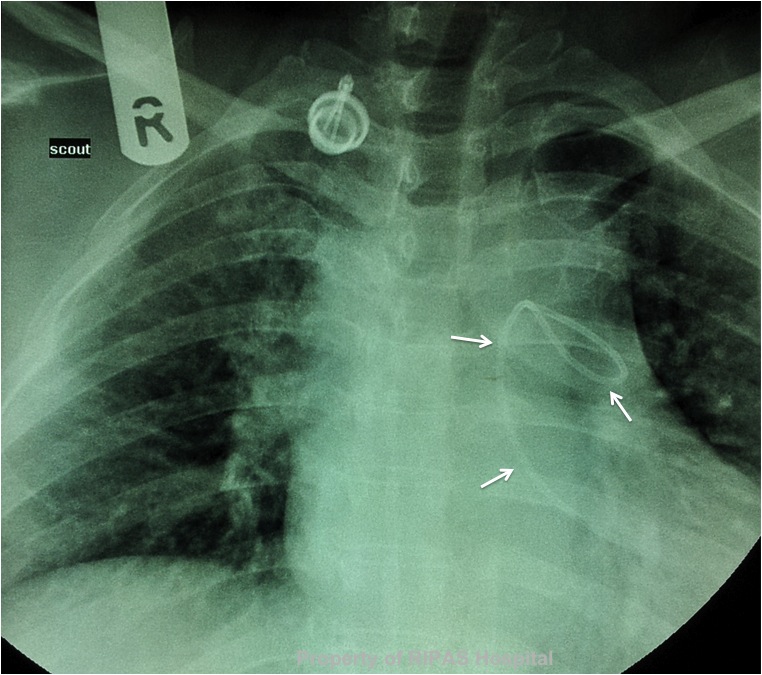

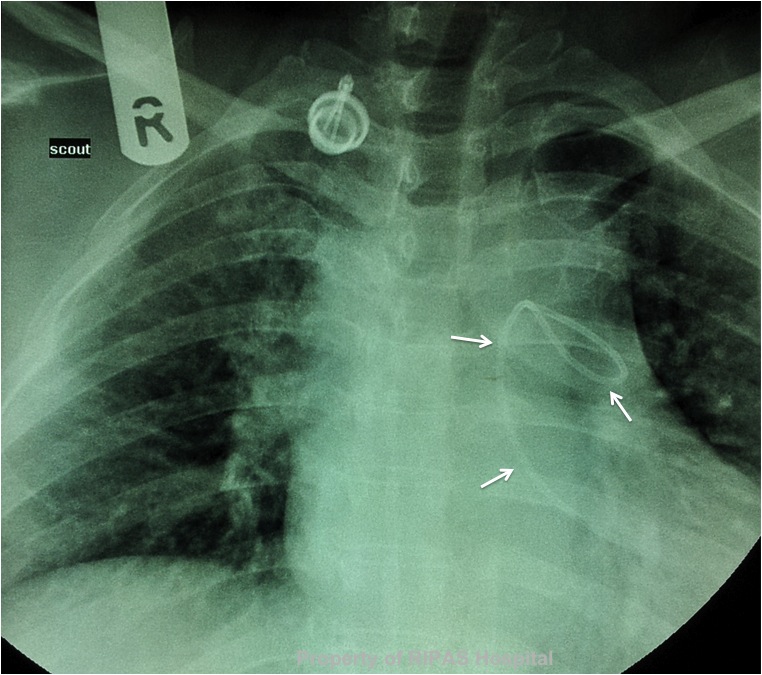

Figure 1: Dislodged port-a-catheter as

indicated by the catheter (white arrows) which is found in the right

ventricle and left pulmonary artery. It is no longer connected to the

port which is found in the right anterior chest wall.

(Click on image to

enlarge) |

|

Dislodgement of port-a-catheter is an uncommon event, with a

reported incidence of about 4.1% to 5.1%.

(1,2)

In a reported series, 42% of the dislodged catheter ended up in the right

ventricle, 33% in the right atrium and 25% in the pulmonary artery. Figure 1

showed a dislodged port-a-catheter, completely disconnected from the main port

in the right anterior chest wall with the proximal end of the catheter resting

in the right ventricle and the distal end looping in the left pulmonary artery.

In 80% of the cases, the patients presented with port-a-catheter

dysfunction and dislodgement confirmed on chest x-rays. In the remaining 20%,

the dislodgement were diagnosed at surgical removal.

Possible mechanism by which dislodgement occurs may be due to

degradation of the catheter material over time, which results in most cases to

fracture of the catheter rather than dislodgement. Over zealous flushing of

port-a-catheter, particularly if the catheter is occluded may result in

stretching and ballooning of the catheter over the snout of the connector of the

port and thus dislodgement. In the case depicted in Figure 1, the patient

reported several months back, feeling a sharp pain with swelling around the port

when the nurse forcefully flushed her port-a-catheter during a follow-up visit.

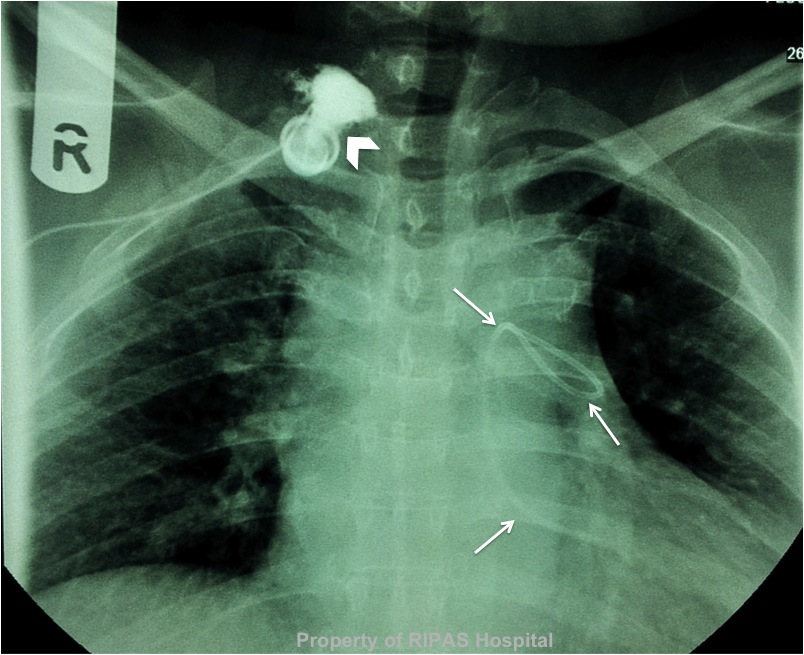

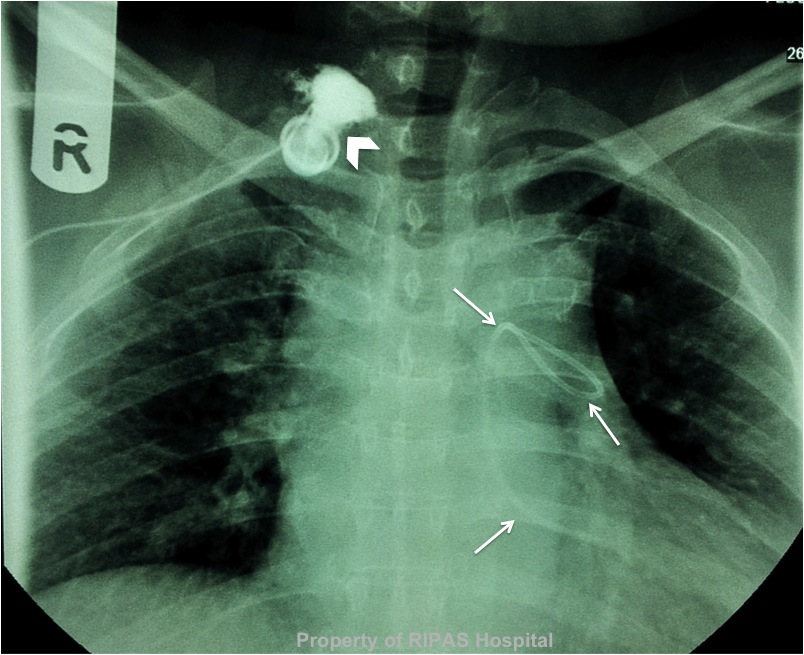

The dislodgement occurred a while back as instillation of contrast into the

port, showed extravasation of contrast into the surround subcutaneous tissue and

not into the vein (Figure 2). The tract between the right internal jugular vein

and the port would have sealed off by then.

|

|

|

Figure 2: Instillation of contrast into the

port resulted in extravasation of the contrast into the surrounding

subcutaneous tissue (white arrow head). The tract between the right

internal jugular vein and the port has completely sealed over.

(Click on image to

enlarge) |

To date, there are very little or no reports of complications

arising from a dislodged catheter, mainly because most of the dislodged or

fracture catheters are removed immediately once they are diagnosed. However,

complications that can arise are related to infection of the catheter,

thrombosis and embolisation or it can migrate further down the pulmonary artery

causing pulmonary embolism of the distal segment of the lung supplied by the

occluded pulmonary artery.

Management of dislodged port-a-cath is usually non-surgical via

transcatheter techniques using a gooseneck snare guidewire under fluoroscopic

guidance in 98%-100% of cases. The catheter is easily removed without

significant complications. Open surgical removal is reserved for failed

percutaneous transcatheter removal and depending on the site at which the

catheter comes to rest, cardiopulmonary bypass may be required. The port is

removed surgically under local anaesthetic.

REFERENCES

1. Coccaro M, Bochicchio AM, Capobianco AM, Di Leo P,

Mancino G, Cammarota A. Long-term infusional systems: complications in cancer

patients. Tumori. 2001 Oct;87(5):308–11.

2. Ho C-L, Chou C-M, Chang T-K, Jan S-L, Lin M-C, Fu Y-C.

Dislodgment of port-a-cath catheters in children. Pediatr Neonatol. 2008

Oct;49(5):179–82.

Images and text contributed and prepared by

Mr William Chong, Thoracic Unit, Department of Surgery, RIPAS Hospital.

All

images are copyrighted and property of RIPAS Hospital.